Hundreds of mythical creatures existed in the minds of ancient man, mostly because in the old days, humans didn’t carry cellphones with cameras. Those days are gone.

There are no fantastic monsters in our world. We know everything. We’ve seen everything. And we have the Instagram accounts to prove it.

But have we seen everything? Perhaps there are still mysteries to discover.

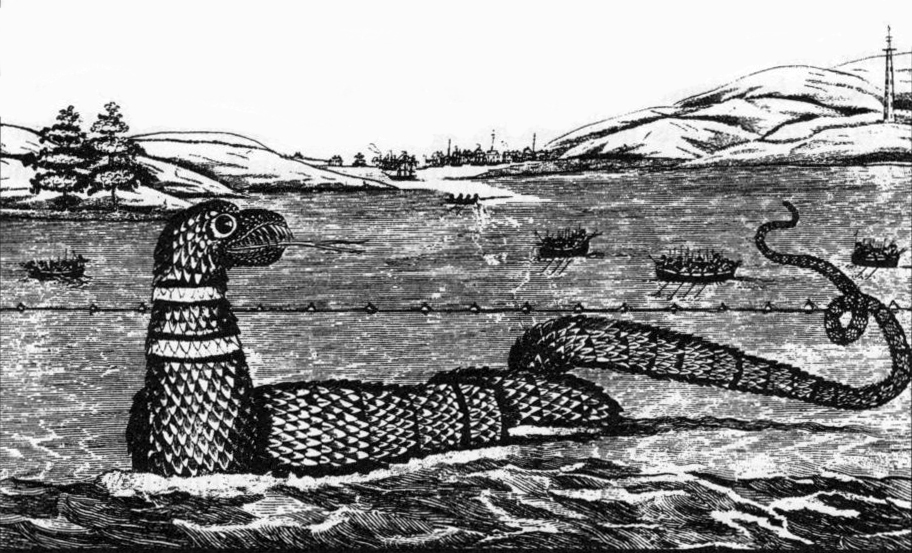

Sea Monsters | Soe Orm

The Soe Orm was first mentioned in 1555 in the famous Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (A Description of the Northern Peoples), written by Olaus Magnus, a writer, cartographer and exiled Catholic ecclesiastic from Sweden. This book featured tales of the dark winters of Sweden, violent currents of the northern waters and beasts of the sea. It fascinated the rest of the world and was immensely popular. In the book, Magnus included the tale of the Soe Orm.

Olaus Magnus described the monster like this: “The beast is 200 feet long and twenty feet wide, with a growth of hairs of two feet in length hanging from the neck, sharp scales of a dark brown color, and brilliant flaming eyes.” Magnus did not conjure this cryptid from his imagination. He based the description on accounts from sailors and other Scandinavians.

Similar sea serpent descriptions were the same all around the world when people talked of sea monsters. Skeptics explain away the existence of monsters (as always) as one of the following…

Possible Explanations

An oarfish:

The oarfish is the longest bony fish on record, measuring as much as forty-five to fifty feet in length. A red cockscomb of spines on the head leads into a red dorsal fin that runs to the tail. Hmm. That does actually look like a sea monster.

A basking shark:

The basking shark can grow to a length of forty feet. In 1808, a badly decomposed carcass washed up on Stronsay, an island in Scotland. It was dubbed a “sea water snake.” Later analysis revealed that it was actually a basking shark, a creature that feeds on plankton and small fish, not sailors on ships.

An Inexplicable Sea Monster

Skeptics, however, could not explain the Gloucester sea serpent.

First reported in the 1600s, the Gloucester sea serpent was seen by hundreds of people from 1817 to 1819 in Gloucester Bay, Massachusetts—including fishermen, military personnel and locals. Onlookers claimed the creature was at least eighty feet long, maybe even a hundred. It had a head like a horse. One person reported that the creature had something that looked like a stick or spear protruding from its head. Some people guessed that it might be a narwhal. A diagram of the shape and size of a narwhal is indicated below, which eliminates that speculation.

So what was it? Just another oarfish? It’s still a mystery.

Basilisk

Don’t laugh. The basilisk was a legendary reptile that could kill with a single glance.

According to Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24 – 79), a Greek naturalist and philosopher, a basilisk hole could be located by spotting scorched earth and shrubs that surrounded its den. The basilisk is sometimes referred to as King of the Serpents or a cockatrice.

A basilisk is a cryptid of many talents (as well as talons). It not only has a deadly stare, it can fly, kill with a venomous bite and breathe fire. It is one of the most feared mythical creatures of all time and is considered the embodiment of evil.

Hmm. I’m not sure the artist quite captured the evil aspect in the illustration above.

Skeptics believe the stories of the basilisk could be based on the cobra. Cobras can kill from a distance by spewing venom at a victim. The spots on their hood could be construed as a face as well. The legs? Well, maybe they were concealed in the critter’s den.

Whatever a basilisk is, it looks like “good eats” for Thanksgiving. Look at those drumsticks!

Mongolian Death Worm

Somewhere in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia lives a legendary menace, the “olgoi-khorkhoi” or Large Intestine Worm. It was first described in 1926 in a book, On the Trail of Ancient Man by Roy Chapman Andrews. In the book, he quotes the Mongolian prime minister as saying, “…It is shaped like a sausage about two feet long, has not head nor leg and it is so poisonous that merely to touch it means instant death. It lives in the most desolate parts of the Gobi Desert.”

In the 1987 book Altajn Tsaadakh Govd, Ivan Mackerle described the worm as “traveling underground, creating waves of sand on the surface which allow it to be detected. The Mongolians say it can kill at a distance, either by spraying a venom at its prey or by means of electric discharge. They say that the worm lives underground, hibernating most of the year except for June and July, when it becomes active. It is also reported that it most often comes to the surface when it rains and the ground is wet.”

It is believed that if you touch any part of the worm, you will suffer tremendous pain and almost immediate death. It preys on camels and lays its eggs in the camel’s intestines. The venom reportedly corrodes metal. Locals say the worm prefers the color yellow.

So don’t trek the Gobi Desert in your Pittsburgh Steeler pants.

When locals who claimed to have glimpsed the “olgoi-khorkhoi” were shown a specimen of the Tartar sand boa, they said that was the creature they had seen. It’s true, the head is not at all prominent.

This monster strikes the fancy of writers, apparently, as it has threatened protagonists in a lot of movies.

Bunyip | Legend or Australian Relic?

Throughout aboriginal Australia, the mythical bunyip has many forms, but one aspect is constant: the creature lives and preys in water—be it swamp, lake, river or stream.

The word bahnyip first appeared in the Sydney Gazette in 1812 to identify a large black animal like a seal, with a terrible voice that “creates terror.” The aborigines said the bunyip was a devil that ate women, children and livestock that wandered too close to the water’s edge.

In 1845, The Geelong Advertiser announced the discovery of fossils found near Geelong with the headline of “Wonderful Discovery of a new Animal.” The article went on to describe the creature as a mixture of bird and alligator, with a head like an emu, a long bill with serrated edges, the body and legs like that of an alligator.

Though the bunyip has long claws, locals say the animal hugs victims to death. In the water, it swims like a frog. On land, it walks on its two hind legs with its head held high. When erect, it is twelve to thirteen feet tall.

Skeptics explain away the bunyip and the fossils attributed to the creature, saying it is some kind of seal, manatee, extinct dirpotodon, giant starfish or swimming dog. Not a single bunyip has ever been captured.

The last recorded sighting of a bunyip was in 1890. A New South Wales man claimed to have shot a white-pelted bunyip at the edge of a lagoon. Unfortunately, it grunted and disappeared into the water.

Too bad the guy owned a cellphone instead of a rifle. He probably killed the last remaining bunyip in Australia.

The Mothman

The Mothman is part of West Virginia folklore. The creature was first reported in the Point Pleasant area between November 15, 1966 and December 15, 1967.

This elusive cryptic was popularized in the 1975 book The Mothman Prophecies by John Keel and then in the 2002 movie of the same name, starring Richard Gere.

As to sightings, among hundreds of people who claimed to have spotted the Mothman, two couples described a “large flying man with ten-foot wings” that followed their car. Other sightings described a large bird with red eyes that glowed like bicycle reflectors.

The local sheriff thought the sightings were related to an unusually large heron he called a shitepoke. Biologists theorized it was a sandhill crane, nearly as tall as a man with a seven-foot wingspan, lost off its migration route and not native to the region.

The photo of the sandhill crane does support the biologist theory. In the photo, the long neck of the crane isn’t that obvious and the red feathers on the head could be misconstrued as glowing red eyes. If it were flying, the long legs would be tucked up and unseen.

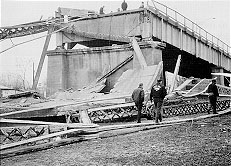

Some believe the Mothman appeared as a harbinger of doom and relate its appearance to the Silver Bridge collapse that killed forty-six people December 15, 1967 during rush hour traffic.

Similar sightings in Russia in 1999 preceded apartment bombings. Apparently, in 2017, fifty-five people claimed they had spotted the creature in Chicago.

According to the sandhill crane migration route map, cranes pass through Chicago and sometimes even fly across the Bering Straits to Russia. So two points for the biologist.

In 1892, a Quebec newspaper ran a story about a young man who shot a “bird-beast” as it descended from the sky. Apparently the creature had feathers on top and fur on the bottom and a fifteen-foot wingspan. Again, the biologist theory rings true that humans mistake large cranes for cryptids.

And humans, unfortunately, are known to shoot things first and ask questions later.

The Kraken

Scandinavian folklore is rife with stories of the Kraken. Norse tales describe a gigantic squid-like creature that lived off the coast of Norway and Greenland and terrorized sailors. The stories most likely came from sightings of the giant squid that live in the area. The giant squid can reach a length of forty to fifty feet.

The first recorded mention of the Kraken was in 1252, in a Norwegian natural history book depicting a creature so large, it was “mistaken for an island.” As late as the 18th century, naturalists were still including the Kraken in their lexicon of sea creatures.

The mythical (and apparently bad-tempered) ship-wrecking, sailor-devouring Kraken lives on in many films, television shows, books and comics, including Moby Dick, Clash of the Titans, Pirates of the Caribbean and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Chimera

A chimera was a female, fire-breathing, hybrid creature from Lycia (southern coast of Turkey). It is depicted as a lion, with the head of a goat protruding from its back, and a tail that may or may not have ended in a snake head.

A chimera had unusual family connections as well as an unusual body. It was the sibling of such monsters as Cerberus, the multi-headed dog with a snake tail and snake protrusions, and the Lernaean Hydra, the multi-headed sea serpent monster. (It seems polycephaly ran in the family.) It was also thought by some to be the mother of the Sphinx. (Apparently polycephaly came from the patriarchal side, as the sphinx has only one head [which some historians claim keeps getting smaller and smaller]). But I digress…(plus I’m running out of parenthetical punctuation choices).

Described in the Iliad as “a thing of immortal make, not human, lion-fronted and snake behind, a goat in the middle, and snorting out the breath of the terrible flame of bright fire.” Similar creatures appeared in Ancient Egyptian, Etruscan, Indus folklore and some medieval works.

Currently chimera is a term used in the fields of biology and genetics to describe a single organism that is formed from two or more zygotes, which results in blood cells of different blood types, and if the zygotes were of differing sexes, then even the possession of both female and male sex organs in one creature.

The Manticore

The manticore was a legendary Persian medieval creature that had the head of a human, body of a lion and a venomous tail that was said to be armed with porcupine quills or scorpion stinger. The manticore could shoot its quills like arrows. It had three rows of teeth, enabling it to eat its prey whole.

What kind of prey did the creature consume? Clue: in Persian, manticore means “man-eater.”

An image of the manticore first appeared in English heraldry in the 15th century, as a badge of William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings. In the 16th century, the manticore was used as a badge by Robert Radcliffe, 1st Earl of Sussex and by Sir Anthony Babyngton.

The Werewolf

The stories of the men and women who turn into wolves are confined to European folklore, but there are many versions of the origin of the beast. Some say the creature first appeared in The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Sumerian poem written during the late second millennium BC. In part of the long poem, a jilted woman turns her ex into a wolf. Another origin story comes from Greek mythology in the story of Lycaon, who was cursed by Zeus and turned into a wolf, along with his sons. In Nordic folklore, a father and son went on a murderous rampage after finding wolf pelts that transformed them into wolves for ten days.

Pagan traditions associated with wolf-men persisted longest among the Vikings. In fact, Harald I (c. 850 – c. 932) of Norway is said to have maintained a fighting force of Ulfhednar (wolf-coated men). These men dressed in wolf hides and channeled the wolf spirit when they stormed into battle. They were immune to pain and were ferocious fighters. The Ulfhednar seems like a plausible explanation for the origin of the legend of the werewolf, as the Vikings ravaged much of Europe at the height of their power, and their wolf-coated soldiers would have spread fear in the hearts of the locals.

Oddly enough, the belief in werewolves and their persecution coincided with the witch-hunts of the 15th and 16th centuries. The last record of a trial involving a werewolf took place in the 18th century.

The Monster of Krakow (Cracow)

The last cryptid on the list is The Monster of Cracow. This deformed child was reportedly born in 1543 or 1547 and is mentioned in a book by cartographer Sebastian Munster.

Munster’s Cosmographia of 1544 was the earliest German-language description of the world and contained intriguing woodcuts by famous German artists of the day. The many illustrations made the book unique and accessible to anyone, which attributed to its popularity.

In his book, Munster wrote that “the Monster of Cracow was born with barking dogs’ heads mounted on its elbows, chest and knees.” Unfortunately, the child lived only four hours. As it died, it reportedly cried out, “Watch, the Lord Cometh.”

It is difficult to believe that a four-hour-old child could speak in complete sentences and harder still to believe the dog head tale. Perhaps the child’s body was composed of multiple conjoined fetuses that were all crying out in pain. The cacophony must have been horrific. And perhaps the religious aspect surrounding the birth was the only medical explanation available at the time.

After all, it was the sixteenth century. A woman’s physician could be her tarot card reader, her astrologer and her pharmacist, all rolled into one. If the man was a quack, she could be unknowingly poisoned, informed that she was a Virgo not a Libran, warned her life would end on Thursday and that her boil was the result of communion with the devil—none of which was true.

This particular cryptid is sad and sobering—and not really a monster at all.